A Modern Reddit Frontend

Note, before you read this wall of text: this is part one of two. This explains the history behind the current stack, not the current stack we're using. For that, wait for the second post (this post will be updated with a link once available.)

Reddit's codebase, colloquially known as "r2", was (is) a decade- old python monolith. When I started two years ago, my role as frontender was mostly relegated to minor UI tweaks; auto-updating timestamps, admin UI changes, and jQuery upgrades. It was a slower-paced codebase than even the hellscape Rails monolith at Airbnb (which isn't to say that either lacked skilled or thoughtful engineers; it's just the inevitability of the monolith, no matter what some people might argue. Don't blame me, I tried to fix it.)

It has become a common theme, in my experience, that after sufficient time and fustration have been spent working within the confines of a monolithic codebase, an excitable frontend engineer will find opportunity to begin something called a "mobile web redesign". This engineer may say, "hey, our mobile web experience is bad. 50% of our users are on mobile devices! Why don't we do something a little different, a little experimental, and see what it would look like on a virgin codebase? We'll use our current API, and if it goes well, we can port our changes to the main codebase. If it fails, well, it's a separate codebase. We'll timebox it and everything." This conversation will generally involve various levels of product managers, engineering managers, and the occasional executive, who will collectively shrug and accept the "50% of users" value as truth. The trouble is, of course, that there's a whole lot of legacy functionality included in any old codebase, and even more in a monolith where code can be monkeypatched and annotated to the point of total incomprehensibility. Compounded by a complete lack of tests, a plugin system that autoloaded routes, and that the engineering team was less than a half-dozen engineers meant that time was ripe for me to begin the same phyrric path that many others before me had wandered.

These thoughts in mind, in September 2014, I created a new github repository called reddit-mobile, and began the decision of how the hell to build this thing. Reddit has a long history of open-sourceness, so whatever I picked had to be just as friendly; not some flavor-of-the-week framework like Meteor[0] or Angular[1] (see footnotes), but something with longevity. Something that was built for the right reasons, that would remain readable at worst, and current at best, several years into the future. Refactorability and choice were prime priorities, but so was getting work done as a single engineer, and later as a small team.

During my time at Airbnb, over many discussions with the frontend team, we came to a conclusion that made a lot of sense: picking a collection of libraries and building the glue around them as a framework makes more sense than picking a framework and building your application around it. This lets you choose the best library for your application and team's needs; languages, linters, build tools, interface with the rest of your stack, and the team's expertise rarely fits with a large framework that makes the decisions for you. In the case of Reddit, I determined the priorities for our frontend web stack to be:

- Accessibility. An advantage of Reddit is that it's easy to read from anywhere; it's just plain HTML. The stack also needs to provide server rendering for SEO (a huge portion of our traffic) and for old and busted devices. And, while the mobile site might be able to get away without a super hardcore accessibility implementation, the libraries I chose should make it easy - because, with an end goal of rebuilding all of Reddit's web properties, we'll want desktop to be able to support everything, from screen readers to Lynx to Chrome dev channel to more esoteric web browsers.

- A great user experience. Fast loads, for one; especially on mobile, when data transfer is slow, ping times are terrible, and CPU and RAM can be in short supply. We also need to balance that with building out rich interactivity; new tools, inline video embeds, and the like. I wanted to build the Reddit that I wanted to browse, and give designers room to experiment with different display formats and flows.

- Developer productivity. Assuming #1 is an unchanging requirement, a small team should be able to rapidly move. So, while Reddit is accessible, it falls short of of achieving velocity on changes. r2 is "change the name of a model, and the CSS breaks" complex. Additionally, there are a lot of plugins, like RES, and custom stylesheets that would break if I started refactoring the r2 frontend directly. Along those lines, I needed to pick a technology that was a) common; b) worked with modern dev practices; and c) could be refactored easily when Chronos spins his wheel and it's time to move on to new versions of our libraries - or new libraries entirely.

To accomplish #1, accessibility, we need to render on the server. Some

frameworks accomplish this by doing things like running WebKit on the server[0],

but that's lazy, doesn't scale well, and is slow. Some frameworks require you to

write in a template language for the back-end, and then either re-implement the

templates in javascript for the client or write jQuery spaghetti code for event

management and UI updates. However, if we pick a template language that can be

rendered on the server and client the same way- template + data = html-

we're in a good place. Our next goal, a great user experience, involves interactivity.

This is accomplished with some kind of UI updating toolkit, which could be take

dozens of forms; jQuery spaghetti, Backbone, Angular, Polymer, and more. As it happens,

it was around this time that React was getting popular. The current codebase

had some Backbone (still does; live threads, for example), but a lot of new

code was being written using React (Reddit Gifts and ad management tools.) To

accomodate the third priority- developer productivity- it made sense to use what

the other frontend devs were interested in, as long as it promoted the other

goals as well. It turns out that it's pretty easy to render React on the

server, and React is perfect for building a highly responsive UI, so the choice

was made pretty easily. The server-side decision was just as easy; if we could

render React in node, then we don't have to write viewmodel, API, or other

miscellaneous library code in two languages. We'd also use ES7+; Babel (then 6to5) was

becoming a solid way to transform bleeding-edge javascript [standards | vague

suggestions] into code the browser could run, so we could get the benefits of

syntax sugar (classes! generators! async/await!) without having to use a

non-javascript langauge, again lowering the barrier to entry and futureproofing

the codebase.

To understand how to get all of these pieces working together, I took a look at how requests were made on the server-side and client-side.

SERVER:

http request -> web server -> router -> API calls -> resolve API calls -> render

CLIENT:

link click -> router -> API calls -> render -> resolve API calls -> render again

The server and client aren't that different - the only glue code necessary is:

- Build a "fake" http request object on the client that matches the web server, so the router doesn't care what environment it's running in;

- Abstract out synchronous data-loading on the server from asynchronous data- loading on the client, so that both environments can operate efficiently. The server shouldn't render pages until it has all the data it needs, but the client can render immediately and update the view as data loads.

I designed horse[2] and a react-specific subclass, horse-react[2] as the middle layer, which looks something like:

http request > middleware >v

v

v<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

v (wait if synchronous)

router > middleware > route > register API calls > render template

^ (watch for updates if async)

^<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

^

link click > middleware >^

I also built an API library, snoode[3] to make dealing with Reddit's unique api design easy, feet[4] for feature flags (turn X on if you're an employee, or turn Y on if there's a querystring flag), and restcache[5] to handle the caching of REST-like API responses.

With this done, building new pages that rendered server-side and client side looked like:

- Write a new route handler, mapping a URL to an asynchronous function. It should set props on the request context object, which will later be passed into a React template, register any API calls that need to be made, and set its page property to a React class. The page will be rendered inside of the layout, with the props you set up in the handler passed into it. Here's an example.

- Write your React template and any necessary components.

- Write any styles you need.

- Build it, and :magic:

This worked for quite some time, and it was very straightforward to add pages. However, as the team and app grew, we noticed a few areas where things got a little messy. It was never clear how best to handle interactions, and especially interactions that took place across components. You could use one of a couple methods, two of which we used heavily:

- Create a handler function in the parent element, and pass it into the child

element. For example, you might have

<CommentSubmissionForm onSubmit={ this.postComment } />, wherepostCommentis owned by the element which containsCommentSubmisisonForm. The trouble is, you'd have to duplicate this comment submission function for any element that containsCommentSubmissionForm- for example, you can post a comment from either thePostitself, or as a reply to anotherComment. You could subclass bothPostandCommentfrom a superClass likeCommentReplyable, but multiple inheritence doesn't exist in Javascript. You could write mixins for classes that append methods to the prototype, but then you still have to pass the code from some level of parent through to some level of child; and all elements in between the component with API access and the submit button itself have to be aware of the heirarchy. It isn't clear exactly who should be making the API call. This lead to a lot of inconsistency. - Create an event. Fire off

app.emit('newComment', commentData }), and have a listener that watches for that event, submits an API change, then emits asuccessorerrorfunction. Again, problem is - you have to write code in both places that watch for thatsuccess, and remember to stop listening when your element is discarded because you moved on to another page.

In either of these cases, you're required to pass in API information, such as your current token, from the top-level all the way through to whichever component actually makes the API call. This gets even more complicated when you have to start pausing API requests when refreshing your OAuth token. Eventually, things got to where we couldn't answer the question of handling intra-component interactivity without taking a second look at how our framework was designed.

Stand by for Part II, whereupon I discuss our use of Redux to solve these issues.

[0] since I began this post, Meteor switched to rendering React and Angular directly on the server, rather than either no server-side rendering or spinning up a WebKit project, and is thus no longer a Poor Choice.

[1] I've always dislked Angular because it shoves a ton of magic into the template layer, and you don't have any visibility into what's going on. I dislike Magic.

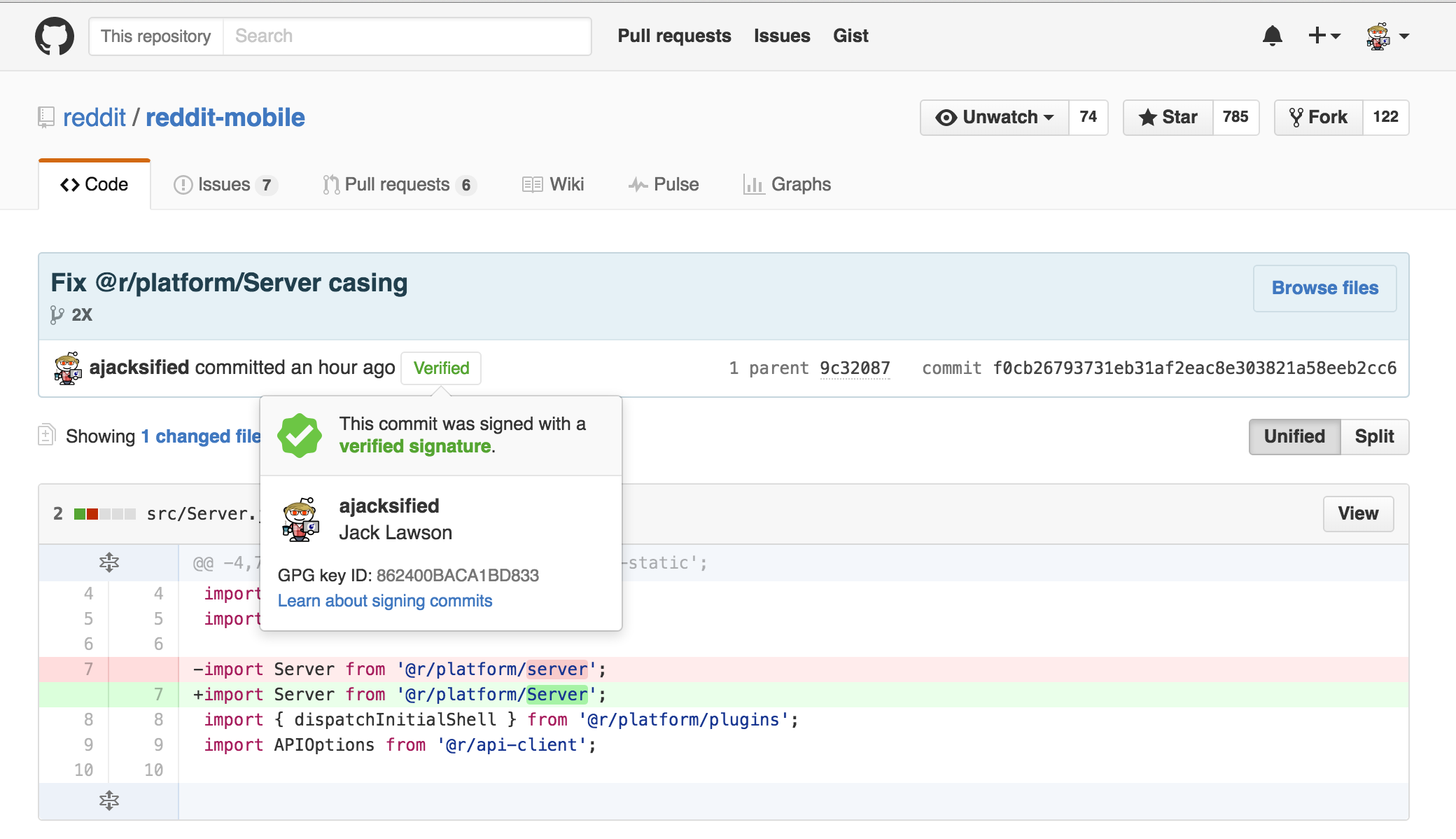

[2] Horse is now deprecated, in favor of node-platform.

[3] Snoode is now found at node-api-client

[4] Feet is now found at node-flags

[5] Restcache is now defunct, replaced by a Redux store.